A criminal profiler working with the FBI was interviewing serial killer Edmund Kemper. Alone. He had no gun on him

A criminal profiler working with the FBI was interviewing serial killer Edmund Kemper. Alone. He had no gun on him. And when he buzzed the guards to collect him… no one came for over half an hour.

Kemper, a 6′9″ and 300 pound man, leaned over and said the following words: “If I went apeshit in here, you’d be in a lot of trouble, wouldn’t you

It was pretty chilling. Because Kemper was a 100% correct — he could harm the profiler. He could absolutely, and with great ease, take his life. The FBI man knew this. He even tried to negotiate a little with Kemper. Told him he’d be in trouble, that he’d be put in solitary… Kemper wasn’t fazed, replying that he’d been in solitary before, and that they would not place him there forever. In fact, killing an FBI officer would only elevate his status among other prisoners, and he knew he would never walk free anyway..

For fifteen minutes that must have felt like hours, Kemper toyed with the profiler. When the guards finally came, he placed a huge hand on the profiler’s shoulder. “You know I was just kidding, don’t you?” he said. No one ever interviewed serial killers alone since

“If I went apeshit in here, you’d be in a lot of trouble, wouldn’t you?”

Supervisory Special Agent and Criminologist Robert K. Ressler, from the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, famously told the story of his third meeting with Ed Kemper:

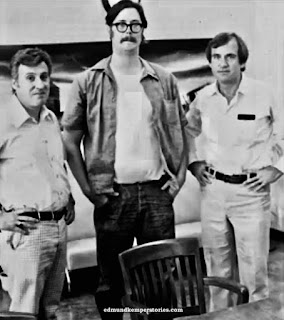

Twice before, I had ventured in the Vacaville prison in California to see and talk with him, the first time accompanied by John Conway, the second time by Conway and by my Quantico associate John Douglas, whom I was breaking in.

During those sessions, we had gone quite deeply into his past, his motivations for murder, and the fantasies that were intertwined with those crimes. (…) I was so pleased at the rapport I had reached with Kemper that I was emboldened to attempt a third session with him alone. It took place in a cell just off death row, the sort of place used for giving a last benediction to a man about to die in the gas chamber. (…)

After conversing with Kemper in this claustrophobic locked cell for four hours, dealing with matters that entail behavior at the extreme edge of depravity, I felt that we had reached the end of what there was to discuss, and I pushed the buzzer to summon the guard to come and let me out of the cell. No guard immediately appeared, so I continued on with the conversation. (…)

After another few minutes had passed, I pressed the buzzer a second time, but still got no response. Fifteen minutes after my first call, I made a third buzz, yet no guard came.

A look of apprehension must have come over my face despite my attempts to keep calm and cool, and Kemper, keenly sensitive to other people’s psyches, picked up on this.

“Relax, they’re changing the shift, feeding the guys in the secure area.” He smiled and got up from his chair, making more apparent his huge size. “Might be fifteen, twenty minutes before they come and get you,” he said to me. (…)

Though I felt I maintained a cool and collected posture,

I’m sure I reacted to this information with somewhat more overt indications of panic, and Kemper responded to these.

“If I went apeshit in here, you’d be in a lot of trouble, wouldn’t you? I could screw your head off and place it on the table to greet the guard.”

My mind raced. I envisioned him reaching for me with his large arms, pinning me to a wall in a stranglehold, and then jerking my head around until my neck was broken. It wouldn’t take long, and the size difference between us would almost certainly ensure that I wouldn’t be able to fight him off very long before succumbing. He was correct: He could kill me before I or anyone else could stop him. So, I told Kemper that if he messed with me, he’d be in deep trouble himself.

“What could they do– cut off my TV privileges?” he scoffed.

I retorted that he would certainly end up “in the hole” – solitary confinement – for an extremely long period of time.

Both he and I knew that many inmates put in the hole are forced by such isolation into at least temporary insanity.

Ed shrugged this off by telling me that he was an old hand at being in prisons, that he could withstand the pain of solitary and that it wouldn’t last forever.

Eventually, he would be returned to a more normal confinement status, and his “trouble” would pale before the prestige he would have gained among the other prisoners by “offing” an FBI agent.

My pulse did the hundred-yard dash as I tried to think of something to say or do to prevent Kemper from killing me. I was fairly sure that he wouldn’t do it but I couldn’t be completely certain, for this was an extremely violent and dangerous man with, as he implied, very little left to lose. How had I been dumb enough to come in here alone?

Suddenly, I knew how I had embroiled myself in such a situation. Of all people who should have known better, I had succumbed to what students of hostage-taking events know as “Stockholm syndrome”- I had identified with my captor and transferred my trust to him. Although I had been the chief instructor in hostage negotiation techniques for the FBI, I had forgotten this essential fact! Next time, I wouldn’t be so arrogant about the rapport I believed I had achieved with a murderer. Next time.

“Ed,” I said, “surely you don’t think I’d come in here without some method of defending myself, do you?”

“Don’t shit me, Ressler. They wouldn’t let you up here with any weapons on you.”

Kemper’s observation, of course, was quite true, because inside a prison, visitors are not allowed to carry weapons, lest these be seized by inmates and used to threaten the guards or otherwise aid an escape. I nevertheless indicated that FBI agents were accorded special privileges that ordinary guards, police, or other people who entered a prison did not share.

What’ve you got then?”

“I’m not going to give away what I might have or where I might have it on me.”

“Come on, come on; what is it – a poison pen?”

“Maybe, but those aren’t the only weapons one could have.”

“Martial arts, then,” Kemper mused. “Karate? Got your black belt? Think you can take me?”

With this, I felt the tide had shifted a bit, if not turned. There was a hint of kidding in his voice – I hoped. But I wasn’t sure, and he understood that I wasn’t sure, and he decided that he’d continue to try and rattle me. By this time, however, I had regained some composure, and thought back to my hostage negotiation techniques, the most fundamental of which is to keep talking and talking and talking, because stalling always seems to defuse the situation. We discussed martial arts, which many inmates studied as a way to defend themselves in the very tough place that is prison, until, at last, a guard appeared and unlocked the cell door. (…)

As Kemper got ready to walk off down the hall with the guard, he put his hand on my shoulder.

“You know I was just kidding, don’t you?”

“Sure,” I said, and let out a deep breath.

I resolved never to put myself or any other FBI interviewer in a similar position again. From then on, it became our policy never to interview a convicted killer or rapist or child molester alone; we’d do that in pairs.

Source: Whoever Fights Monsters – My twenty years tracking serial killers for the FBI, by Robert K. Ressler and Tom Shachtman, 1992

Comments

Post a Comment